So, new research shows that a) LLM-type “AI” chatbots are extremely persuasive and able to get voters to shift their positions, and that b) the more effective they are at that, the less they hew to factual reality.

Which: Yeah. A bunch of us told you this.

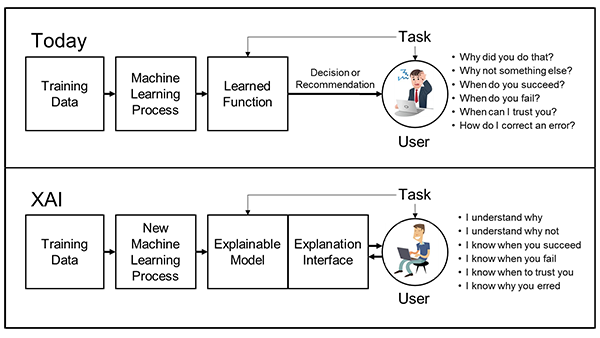

Again: the Purpose of LLM- type “AI” is not to tell you the truth or to lie to you, but to provide you with an answer-shaped something you are statistically determined to be more likely to accept, irrespective of facts— this is the reason I call them “bullshit engines.” And it’s what makes them perfect for accelerating dis- and misinformation and persuasive propaganda; perfect for authoritarian and fascist aims of destabilizing trust in expertise. Now, the fear here isn’t necessarily that candidate A gets elected over candidate B (see commentary from the paper authors, here). The real problem is the loss of even the willingness to try to build shared consensus reality— i.e., the “AI” enabled epistemic crisis point we’ve been staring down for about a decade.

Other preliminary results show that overreliance on “generative AI” actively harms critical thinking skills, degrading not just trust in, but the ability to critically engage with, determine the value of, categorize, and intentionally sincerely consider new ways of organizing and understanding facts to produce knowledge. Further, users actively reject less sycophantic versions of “AI” and get increasingly hostile toward/less likely to help or be helped by other actual humans because said humans aren’t as immediately sycophantic. And thus, taken together, these factors create cycles of psychological (and emotional) dependence on tools that Actively Harm Critical Thinking And Human Interaction.

What better dirt in which for disinformation to grow?

The design, cultural deployment, embedded values, and structural affordances of “AI” has also been repeatedly demonstrated to harm both critical skills development and now also the structure and maintenance of the fabric of social relationships in terms of mutual trust and the desire and ability to learn from each other. That is, students are more suspicious of teachers who use “AI,” and teachers are still, increasingly, on edge about the idea that their students might be using “AI,” and so, in the inimitable words and delivery of Kurt Russell:

Combine all of the above with what I’ve repeatedly argued about the impact of “AI” on the spread of dis- and misinformation, consensus knowledge-making, authoritarianism, and the eugenicist, fascist, and generally bigoted tendencies embedded in all of it—and well… It all sounds pretty anti-pedagogical and anti-social to me.

And I really don’t think it’s asking too much to require that all of these demonstrated problems be seriously and meticulously addressed before anyone advocating for their implementation in educational and workplace settings is allowed to go through with it.

Like… That just seems sensible, no?

The current paradigm of “AI” encodes and recapitulates all of these things, but previous technosocial paradigms did too, and if these facts had been addressed back then, in the culture of technology specifically and our sociotechnical culture writ large, then it might not still be like that, today.

But it also doesn’t have to stay like this. It genuinely does not.

We can make these tools differently. We can train people earlier and more consistently to understand the current models of “AI,” reframing notions of “AI Literacy” away from “how to use it” and toward an understanding of how they functions and what they actually can and cannot do. We can make it clear that what they produce is not truth, not facts, not even lies, but always bullshit, even when they seem to conform to factual reality. We can train people— students, yes, but also professionals, educators, and wider communities— to understand how bias confirmation and optimization work, how propaganda, marketing, and psychological manipulation work.

The more people learn about what these systems do, what they’re built from, how they’re trained, and the quite frankly alarming amount of water and energy it has taken and is projected to take to develop and maintain them, the more those same people resist the force and coercion that corporations and even universities and governments think pass for transparent, informed, meaningful consent.

Like… researchers are highlight that the current trajectory of “AI” energy and water use will not only undo several years of tech sector climate gains, but will also prevent corporations such as Google, Amazon, and Meta from meeting carbon-neutral and water-positive goals. And that’s without considering the infrastructural capture of those resources in the process of building said data centers, in the first place (the authors list this as being outside their scope); with that data, the picture is worse.

As many have noted, environmental impacts are among the major concerns of those who say that they are reticent to use or engage with all things “artificial intelligence”— even sparking public outcry across the country, with more people joining calls that any and all new “AI” training processes and data centers be built to run on existing and expanded renewables. We are increasingly finding the general public wants their neighbours and institutions to engage in meaningful consideration of how we might remediate or even prevent “AI’s” potential social, environmental, and individual intellectual harms.

But, also increasingly, we find that institutional pushes— including the conclusions of the Nature article on energy use trends— tend toward an “adoption and dominance at all costs” model of “AI,” which in turn seem to be founded on the circular reasoning that “we have to use ‘AI’ so that and because it will be useful.” Recurrent directives from the federal government like the threat to sue any state that regulates “AI,” the “AI Action Plan,” and the Executive Order on “Preventing Woke AI In The Federal Government” use term such as “woke” and “ideological bias” explicitly to mean “DEI,” “CRT,” “transgenderism,” and even the basic philosophical and sociological concept of intersectionality. Even the very idea of “Criticality” is increasingly conflated with mere “negativity,” rather than investigation, analysis, and understanding, and standards-setting bodies’ recommendations are shelved before they see the light of day.

All this even as what more and more people say they want and need are processes which depend on and develop nuanced criticality— which allow and help them to figure out how to question when, how, and perhaps most crucially whether we should make and use “AI” tools, at all. Educators, both as individuals and in various professional associations, seem to increasingly disapprove of the uncritical adoption of these same models and systems. And so far roughly 140 technology-related organizations have joined a call for a people- rather than business-centric model of AI development.

Nothing about this current paradigm of “AI” is either inevitable or necessary. We can push for increased rather than decreased local, state, and national regulatory scrutiny and standards, and prioritize the development of standards, frameworks, and recommendations designed to prevent and repair the harms of “generative AI.” Working together, we can develop new paradigms of “AI” systems which are inherently integrated with and founded on different principles, like meaningful consent, sustainability, and deep understandings of the bias and harm that can arise in “AI,” even down to the sourcing and framing of training data.

Again: Change can be made, here. When we engage as many people as possible, right at the point of their increasing resistance, in language and concepts which reflect their motivating values, we can gain ground towards new ways of building “AI” and other technologies.

![Screenshot of ChatpGPT page:ChaptGPT Promo: 2 months free for students ChatGPT Plus is now free for college students through May Offer valid for students in the US and Canada [Buttons reading "Claim offer" and "learn more" An image of a pencil scrawling a scribbly and looping line] ChatGPT Plus is here to help you through finals](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_fullsize/plain/did:plc:ybkylffhwhn2an2ic2lxh76k/bafkreidh6mhffosfxhbgnxx6aybjycvgj3c2ygzto2xhzvsohdsv3g6evm@jpeg)