Much of my research deals with the ways in which bodies are disciplined and how they go about resisting that discipline. In this piece, adapted from one of the answers to my PhD preliminary exams written and defended two months ago, I “name the disciplinary strategies that are used to control bodies and discuss the ways that bodies resist those strategies.” Additionally, I address how strategies of embodied control and resistance have changed over time, and how identifying and existing as a cyborg and/or an artificial intelligence can be understood as a strategy of control, resistance, or both.

In Jan Golinski’s Making Natural Knowledge, he spends some time discussing the different understandings of the word “discipline” and the role their transformations have played in the definition and transmission of knowledge as both artifacts and culture. In particular, he uses the space in section three of chapter two to discuss the role Foucault has played in historical understandings of knowledge, categorization, and disciplinarity. Using Foucault’s work in Discipline and Punish, we can draw an explicit connection between the various meanings “discipline” and ways that bodies are individually, culturally, and socially conditioned to fit particular modes of behavior, and the specific ways marginalized peoples are disciplined, relating to their various embodiments.

This will demonstrate how modes of observation and surveillance lead to certain types of embodiments being deemed “illegal” or otherwise unacceptable and thus further believed to be in need of methodologies of entrainment, correction, or reform in the form of psychological and physical torture, carceral punishment, and other means of institutionalization.

Locust, “Master and Servant (Depeche Mode Cover)”

When Black and Indigenous people of color (BIPoC), for instance, are placed into systems of surveillance and subject to hundreds of years of police action and state government violence at higher rates, after having been literally stolen from their lands and culture, this cannot be understood as anything other than efforts toward control. The institutionalization, sterilization, and “behavioral correction” of disabled and neurodiverse populations all also stem from a desire to control and “correct” embodiments which were—and often still are—understood by the wider population as “defects.” Similarly, government-maintained lists of benefits distributions for the disabled and poor, lists which mandate certain styles of life and levels of income, mean that many people cannot get married to or even live with long term partners, for fear of losing life-saving healthcare assistance.

People with uteri, regardless of gender, have been subject to the curtailing of their reproductive freedoms and bodily autonomy for thousands of year, with their struggles playing out in law and policy. LGBTQIA+ and especially gender nonconforming (GNC) individuals are subject to calls to “correct” their thinking and behavior, either through behavioral therapy, electroshock, or, in extreme cases, sterilization and death. Immigrants and native citizens of certain heritages are put on watch lists, and their movements, purchases, and associations are all monitored. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but it provides an example of what it means to be made subject to disciplinary control; the program of social reinforcement—via discourses, media narratives, and educational framings of, e.g., federal texts books—then provides a substrate on which these systems take root and grow.

From educational contexts to carceral systems of justice, societies have historically worked to reinforce an understanding of the “right kind” of person—even extending into which kind of person is the “right kind” for certain types of knowledges, vocations, and professions. There is a known history of the failure to retain women in STEM fields as a result of certain kinds of signals being sent to women about how they ought to behave and what counted as acceptable kinds of “women’s work.” In many cases, women who got ideas beyond the boundaries of what was considered acceptable for them were then put into institutional mental care against their will. Women were even pushed out of computer programing fields, even though they literally founded them. Similar histories can be found regarding the lack of representation of PoC in academia, as a whole, and the reason for this is that even the definition of what counts as the “right kind” of learner has been constructed by a certain type of lived experiential perspective.

[Left: Katherine Johnson working as a computer (“one who computes”) at NASA in 1966 (Credit: NASA); Right: Grace Murray Hopper, in her office in Washington DC in 1978; (Credit: Lynn Gilbert)]

Throughout history, the perspective of affluent, white, able-bodied, cisgender, heterosexual men has been inscribed and reinforced in the building of the academic process and, to the extent that people who do not fit that profile have managed to succeed, it has been because they have shaped their worldview and their epistemological methods to match the dominant mode. Anyone who does not shape themselves so and who then subsequently fails to meet expectations is said to have simply been unable to hack it, in the academy, rather than recognizing that different modes of learning and education might also be valid. As Harriet Washington notes in her book Medical Apartheid¸ specific measures have often been taken to exclude Black people and other non-white groups from fields of expertise, and to denigrate their expertise when it manages to be obtained. Additionally, fields of knowledge from modern medicine back to ancient Greek philosophy have always been rife with prejudicial assumptions about the “proper” nature of both the learning subject, and the object of study.

Strategies for resisting systems of control can include non-violent protest such as the sit-ins of the Black civil rights movements of the 1950’s and 60’s, and the die-ins at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980’s. Groups have also practiced armed march demonstrations, and direct action protests, as well as organizing educational actions to inform people of their rights and of methods of self-defense and harm minimization, in the event that they might be attacked during rallies and marches. The citation of rights and the refusal of illegal searches are other tactics deployed to stymie mechanisms of carceral bodily control but, like any of the above, these strategies are not guaranteed to prevent those in positions of power from oppressing whomever they chose; these strategies will instead only mitigate the likelihood of oppression.

Historical evidence and the present moment both suggest that white, armed, and largely male protestors demanding the freedom to engage in capitalism will, in America and much of the West, be given far more leeway by the disciplinary arm of the state than what would be afforded to LGBTQIA+ folx, disabled folx, people of color, women, and GNC individuals demonstrating for, say, restorative, liberatory, anti-capitalist, or climate justice.

To that end, many communities of care have organized themselves around understanding the needs of their community, whether based in gender, race, disability, sexuality, or overall marginalization, and those communities have worked to build political and institutional power of their own, to countermand that of dominant oppressive forces. Some examples of this include the calls to the decolonization of academic disciplines, and of academia as a whole, where what is meant by “decolonization” is the removal of colonialist ideologies of moving into another’s space, exercising power over them, and extracting their resources to one’s own ends. Work has been done to decolonize the STEM and humanities fields and their pedagogies, and working to then actively introduce Indigenous, post-colonial, or de-colonial knowledge systems and methodologies into them, often hinged on questioning fundamental assumptions about what counts as knowledge. If, for example, lived bodily experience is excluded at the outset from being considered as knowledge, as so often happens in colonial Western studies, then we will lose whole realms of relevant insights about the world and how to exist in it.

Every strategy of bodily and social control we’ve discussed has persisted into the twenty-first century, and most of them have taken on new valences and modes of operation with the advent of changing technologies. Technological artifacts and systems such as computerized databases, algorithmic pattern extrapolation, and biometric surveillance have made it possible to track and collate movements of groups and individuals, and then to build whole systems to serve or exploit those groups and the patterns found therein. In everything from grade management systems which work to entrain behavior without addressing students’ core needs and challenges, to advertising algorithms which are capable suggesting, say, neonatal vitamins based on patterns it recognized in your search engine history, to facial recognition systems which claim to be able to determine whether someone is gay, technology is clearly at play in the operations of oppressive systems.

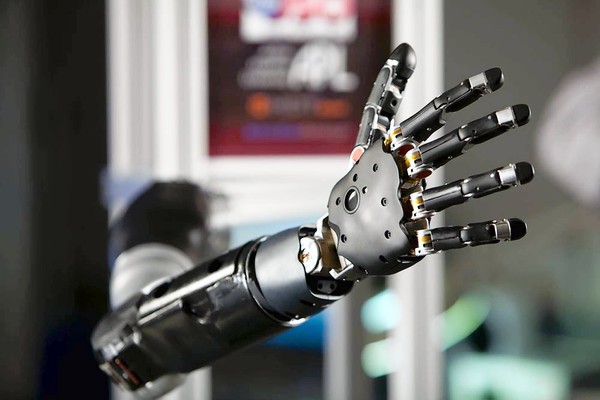

[Image of a prosthetic arm developed by Johns Hopkins University; many full arm amputees have noted that such a device could easily be too heavy.]

Before continuing, I want to clarify that I will primarily be talking about the idea of “cyborgs” in the context of marginalized identities who need to interface with technological systems in order to survive. Cyborg, here, marks that porous space where technologies of control and assemblages of identity interface directly with people’s lived, embodied experience. This sits in direct tension with the notion held by many “cyborg anthropologists” who argue that every twenty-first century human is a cyborg because of our reliance on and interconnection or interrelationship with technology.

Instead, I join others such as Jillian Weise who argue that to be a cyborg necessitates the conscious, literally necessary interface of technology with organic life, in order to facilitate a mode of being which used to be unconscious—this is also the sense which most closely hews to Kline and Clynes’ original definitions of “Cybernetic Organism.” This also means that I will primarily be filtering this discussion of cyborg nature through disability studies, but will also necessarily touch on other forms of marginalization as well, as being Black, or having a uterus, or operating the system of society to be better perceived as your gender identity, or even pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV can all be argued to fit under that rubric. All of that being said, we can understand cyborg being as both a strategy of control and a strategy of resistance.

To be a cyborg, in the framework of the twenty-first century, is to be interfaced with technological artifacts and systems, and in the twenty-first century in the West, that is synonymous with being monitored and surveilled. Devices like Port-A-Cath for chemotherapy patients, transdermal insulin pumps for diabetics, or prosthetic limbs all require maintenance and that maintenance can, for the most part, only be done in the care of trained, licensed professionals. More likely than not, there will be a file of all maintenance and device requests a person makes, a file which could easily be used to surveil, monitor, and control someone’s available range of bodily operations, and their very life. Additionally, treatments and devices marketed to disabled and chronically ill individuals necessarily make them subject to medicalization and institutionalizations of control which seek to regularize and “normalize” their bodies, to make them function the “right way,” and making them have to pay for the privilege, to boot.

But all of the above circumstances have also motivated the development of cyborg strategies of resistance—individuals and groups who hack their own bodies to make them what they and their community need them to be to survive in societies which are in many cases structured against that survival. Biohacking communities of diabetics who make their own insulin; support groups and communities of practice which share information among their members like system hacks for benefits and insurance; political action networks which develop strategies to use their physical embodiment as wheelchair users to block physical access to government buildings; and those who use their physical embodiment to impede the functioning of digital and algorithmic systems. Facial recognition systems have a hard time seeing Black people or recognizing changes in facial structures that come with conditions like cerebral palsy, and so some Black and disabled activists have advocated for simply not being included, to reduce the chances of being algorithmically surveilled and targeted.

[Image of a computer case with three red dots in a triangular formation, from the television series Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles]

Right now, AI is an algorithmic cop, and so the carceral, corporate, and militarized principles embodied in their projects will form the foundation for any machine mind developed from it. However, militarized, carceral capitalism alone is not the cause of these problems. Racism, ableism, misogyny, transphobia, homophobia, and all other flavours of bigotry will very much continue to exist in even socialist systems, thus continuing to be baked into our technologies, if they are not actively named, argued against, and dismantled.

Which is why many activists, researchers, and others are working specifically to counteract and prevent military, capitalist, carceral, and even outright white supremacist groups from building their principles into these systems, and to build decolonial, anti-racist, crip, anti-misogynist, and queer principles into the development of algorithmic and other technological systems. If the work to build this form of AI succeeds, however, not only will it thus create and embody new strategies of resistance, but any conscious machine mind which eventually arises from these efforts will itself need such strategies for its own life, as it will almost certainly be immediately deemed by Western society to be the “wrong kind” of person.

Cite as [Williams, Damien P. “Master and Servant: Disciplinarity and the Implications of AI and Cyborg Identity.” A Future Worth Thinking About (Blog). May 4, 2020. [Date Accessed]. https://afutureworththinkingabout.com/?p=5499]