There’s increasing reportage about IBM using Watson to correlate medical data. We’ve talked before about the potential hazards of this:

Do you know someone actually had the temerity to ask [something like] “What Does Google Having Access to Medical Records Mean For Patient Privacy?” [Here] Like…what the fuck do you think it means? Nothing good, you idiot!

Disclosures and knowledges can still make certain populations intensely vulnerable to both predation and to social pressures and judgements, and until that isn’t the case, anymore, we need to be very careful about the work we do to try to bring those patients’ records into a sphere where they’ll be accessed and scrutinized by people who don’t have to take an oath to hold that information in confidence. ‘

We are more and more often at the intersection of our biological humanity and our technological augmentation, and the integration of our mediated outboard memories only further complicates the matter. As it stands, we don’t quite yet know how to deal with the question posed by Motherboard, some time ago (“Is Harm to a Prosthetic Limb Property Damage or Personal Injury?”), but as we build on implantable technologies, advanced prostheses, and offloaded memories and augmented capacities we’re going to have to start blurring the line between our bodies, our minds, and our concept of our selves. That is, we’ll have to start intentionally blurring it, because the vast majority of us already blur it, without consciously realising that we do. At least, those without prostheses don’t realise it.

Dr Ashley Shew, out of Virginia Tech, works at the intersection of philosophy, tech, and disability. I first encountered her work, at the 2016 IEEE Ethics Conference in Vancouver, where she presented her paper “Up-Standing, Norms, Technology, and Disability,” a discussion of how ableism, expectations, and language use marginalise disabled bodies. Dr Shew is, herself, disabled, having had her left leg removed due to cancer, and she gave her talk not on the raised dias, but at floor-level, directly in front of the projector. Her reason? “I don’t walk up stairs without hand rails, or stand on raised platforms without guards.”

Dr Shew notes that users of wheelchairs consider those to be fairly integral extensions and interventions. Wheelchair users, she notes, consider their chairs to be a part of them, and the kinds of lawsuits engaged when, for instance, airlines damage their chairs, which happens a great deal. While we tend to think of the advents of technology allowing for the seamless integration of our technology and bodies, the fact is that well-designed mechanical prostheses, today, are capable becoming integrated into the personal morphic sphere of a person, the longer they use it. And this can extended sensing can be transferred from one device to another. Shew mentions a friend of hers:

She’s an amputee who no longer uses a prosthetic leg, but she uses forearm crutches and a wheelchair. (She has a hemipelvectomy, so prosthetics are a real pain for her to get a good fit and there aren’t a lot of options.) She talks about how people have these different perceptions of devices. When she uses her chair people treat her differently than when she uses her crutches, but the determination of which she uses has more to do with the activities she expects for the day, rather than her physical wellbeing.

But people tend to think she’s recovering from something when she moves from chair to sticks.

She has been an [amputee] for 18 years.

She has/is as recovered as she can get.

In her talk at IEEE, Shew discussed the fact that a large number of paraplegics and other wheelchair users do not want exoskeletons, and those fancy stair-climbing wheelchairs aren’t covered by health insurance. They’re classed as vehicles. She said that when she brought this up in the class she taught, one of the engineers left the room looking visibly distressed. He came back later and said that he’d gone home to talk to his brother with spina bifida, who was the whole reason he was working on exoskeletons. He asked his brother, “Do you even want this?” And the brother said, basically, “It’s cool that you’re into it but… No.” So, Shew asks, why are these technologies being developed? Transhumanists and the military. Framing this discussion as “helping our vets” makes it a noble cause, without drawing too much attention to the fact that they’ll be using them on the battlefield as well.

All of this comes back down and around to the idea of biases ingrained into social institutions. Our expectations of what a “normal functioning body” is gets imposed from the collective society, as a whole, a placed as restrictions and demands on the bodies of those whom we deem to be “malfunctioning.” As Shew says, “There’s such a pressure to get the prosthesis as if that solves all the problems of maintenance and body and infrastructure. And the pressure is for very expensive tech at that.”

So we are going to have to accept—in a rare instance where Robert Nozick is proven right about how property and personhood relate—that the answer is “You are damaging both property and person, because this person’s property is their person.” But this is true for reasons Nozick probably would not think to consider, and those same reasons put us on weirdly tricky grounds. There’s a lot, in Nozick, of the notion of property as equivalent to life and liberty, in the pursuance of rights, but those ideas don’t play out, here, in the same way as they do in conservative and libertarian ideologies. Where those views would say that the pursuit of property is intimately tied to our worth as persons, in the realm of prosthetics our property is literally simultaneously our bodies, and if we don’t make that distinction, then, as Kirsten notes, we can fall into “money is speech” territory, very quickly, and we do not want that.

Because our goal is to be looking at quality of life, here—talking about the thing that allows a person to feel however they define “comfortable,” in the world. That is, the thing(s) that lets a person intersect with the world in the ways that they desire. And so, in damaging the property, you damage the person. This is all the more true if that person is entirely made of what we are used to thinking of as property.

And all of this is before we think about the fact implantable and bone-bonded tech will need maintenance. It will wear down and glitch out, and you will need to be able to access it, when it does. This means that the range of ability for those with implantables? Sometimes it’s less than that of folks with more “traditional” prostheses. But because they’re inside, or more easily made to look like the “original” limb, we observers are so much more likely to forget that there are crucial differences at play in the ownership and operation of these bodies.

There’s long been a fear that, the closer we get to being able to easily and cheaply modify humans, we’ll be more likely to think of humanity as “perfectable.” That the myth of progress—some idealized endpoint—will be so seductive as to become completely irresistible. We’ve seen this before, in the eugenics movement, and it’s reared its head in the transhumanist and H+ communities of the 20th and 21st centuries, as well. But there is the possibility that instead of demanding that there be some kind of universally-applicable “baseline,” we intently focused, instead, on recognizing the fact that just as different humans have different biochemical and metabolic needs, process, capabilities, preferences, and desires, different beings and entities which might be considered persons are drastically different than we, but no less persons?

Because human beings are different. Is there a general framework, a loosely-defined line around which we draw a conglomeration of traits, within which lives all that we mark out as “human”—a kind of species-wide butter zone? Of course. That’s what makes us a fucking species. But the kind of essentialist language and thinking towards which we tend, after that, is reductionist and dangerous. Our language choices matter, because connotative weight alters what people think and in what context, and, again, we have a habit of moving rapidly from talking about a generalized framework of humanness to talking about “The Right Kind Of Bodies,” and the “Right Kind Of Lifestyle.”

And so, again, again, again, we must address problems such as normalized expectations of “health” and “Ability.” Trying to give everyone access to what they might consider their “best” selves is a brilliant goal, sure, whatever, but by even forwarding the project, we run the risk of colouring an expectation of both what that “best” is and what we think it “Ought To” look like.

Some people need more protein, some people need less choline, some people need higher levels of phosphates, some people have echolocation, some can live to be 125, and every human population has different intestinal bacterial colonies from every other. When we combine all these variables, we will not necessarily find that each and every human being has the same molecular and atomic distribution in the same PPM/B ranges, nor will we necessarily find that our mixing and matching will ensure that everyone gets to be the best combination of everything. It would be fantastic if we could, but everything we’ve ever learned about our species says that “healthy human” is a constantly shifting target, and not a static one.

We are still at a place where the general public reacts with visceral aversion to technological advances and especially anything like an immediated technologically-augmented humanity, and this is at least in part because we still skirt the line of eugenics language, to this day. Because we talk about naturally occurring bio-physiological Facts as though they were in any way indicative of value, without our input. Because we’re still terrible at ethics, continually screwing up at 100mph, then looking back and going, “Oh. Should’ve factored that in. Oops.”

But let’s be clear, here: I am not a doctor. I’m not a physiologist or a molecular biologist. I could be wrong about how all of these things come together in the human body, and maybe there will be something more than a baseline, some set of all species-wide factors which, in the right configuration, say “Healthy Human.” But what I am is someone with a fairly detailed understanding of how language and perception affect people’s acceptance of possibilities, their reaction to new (or hauntingly-familiar-but-repackaged) ideas, and their long-term societal expectations and valuations of normalcy.

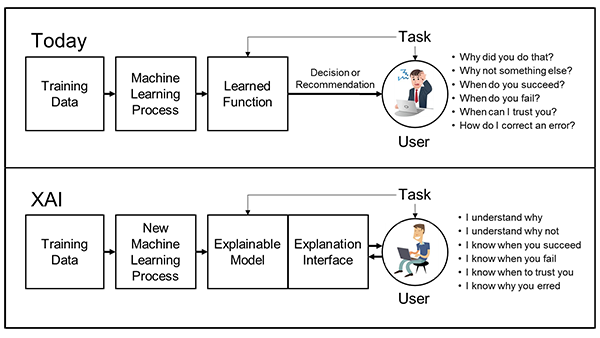

And so I’m not saying that we shouldn’t augment humanity, via either mediated or immediated means. I’m not saying that IBM’s Watson and Google’s DeepMind shouldn’t be tasked with the searching patient records and correlating data. But I’m also not saying that either of these is an unequivocal good. I’m saying that it’s actually shocking how much correlative capability is indicated by the achievements of both IBM and Google. I’m saying that we need to change the way we talk about and think about what it is we’re doing. We need to ask ourselves questions about informed patient consent, and the notions of opting into the use of data; about the assumptions we’re making in regards to the nature of what makes us humans, and the dangers of rampant, unconscious scientistic speciesism. Then, we can start to ask new questions about how to use these new tools we’ve developed.

With this new perspective, we can begin to imagine what would happen if we took Watson and DeepDream’s ability to put data into context—to turn around, in seconds, millions upon millions (billions? Trillions?) of permutations and combinations. And then we can ask them to work on tailoring genome-specific health solutions and individualized dietary plans. What if we asked these systems to catalogue literally everything we currently knew about every kind of disease presentation, in every ethnic and regional population, and the differentials for various types of people with different histories, risk factors, current statuses? We already have nanite delivery systems, so what if we used Google and IBM’s increasingly ridiculous complexity to figure out how to have those nanobots deliver a payload of perfectly-crafted medical remedies?

But this is fraught territory. If we step wrong, here, we are not simply going to miss an opportunity to develop new cures and devise interesting gadgets. No; to go astray, on this path, is to begin to see categories of people that “shouldn’t” be “allowed” to reproduce, or “to suffer.” A misapprehension of what we’re about, and why, is far fewer steps away from forced sterilization and medical murder than any of us would like to countenance. And so we need to move very carefully, indeed, always being aware of our biases, and remembering to ask those affected by our decisions what they need and what it’s like to be them. And remembering, when they provide us with their input, to believe them.