Kirsten and I spent the week between the 17th and the 21st of September with 18 other utterly amazing people having Chatham House Rule-governed conversations about the Future of Artificial Intelligence.

We were in Norway, in the Juvet Landscape Hotel, which is where they filmed a lot of the movie Ex Machina, and it is even more gorgeous in person. None of the rooms shown in the film share a single building space. It’s astounding as a place of both striking architectural sensibility and also natural integration as they built every structure in the winter to allow the dormancy cycles of the plants and animals to dictate when and where they could build, rather than cutting anything down.

And on our first full day here, Two Ravens flew directly over my and Kirsten’s heads.

Yes.

[Image of a rainbow rising over a bend in a river across a patchy overcast sky, with the river going between two outcropping boulders, trees in the foreground and on either bank and stretching off into the distance, and absolutely enormous mountains in the background]

I am a fortunate person. I am a person who has friends and resources and a bloody-minded stubbornness that means that when I determine to do something, it will more likely than not get fucking done, for good or ill.

I am a person who has been given opportunities to be in places many people will never get to see, and have conversations with people who are often considered legends in their fields, and start projects that could very well alter the shape of the world on a massive scale.

Yeah, that’s a bit of a grandiose statement, but you’re here reading this, and so you know where I’ve been and what I’ve done.

I am a person who tries to pay forward what I have been given and to create as many spaces for people to have the opportunities that I have been able to have.

I am not a monetarily wealthy person, measured against my society, but my wealth and fortune are things that strike me still and make me take stock of it all and what it can mean and do, all over again, at least once a week, if not once a day, as I sit in tension with who I am, how the world perceives me, and what amazing and ridiculous things I have had, been given, and created the space to do, because and in violent spite of it all.

So when I and others come together and say we’re going to have to talk about how intersectional oppression and the lived experiences of marginalized peoples affect, effect, and are affected and effected BY the wider techoscientific/sociotechnical/sociopolitical/socioeconomic world and what that means for how we design, build, train, rear, and regard machine minds, then we are going to have to talk about how intersectional oppression and the lived experiences of marginalized peoples affect, effect, and are affected and effected by the wider techoscientific/sociotechnical/sociopolitical/socioeconomic world and what that means for how we design, build, train, rear, and regard machine minds.

So let’s talk about what that means.

While working together to create this space, we had a lot of really good, important, and difficult but far too short conversations at various intersectionalities of race, neurodiversity, disability, gender, class, and AI. We talked about the ways in which these issues matter from the cultural grounding in which we even try to have these conversations and build these systems, to the team members involved, to issues of consent and how these systems will express themselves, to how we’ll understand and watch or listen to or read the output of these systems and then seek to truly understand what’s been communicated to us. We brought in tools from many different disciplines and perspectives, from design to project management to philosophy to sociology to journalism to game design and fabrication to fiction writing to illustration and other visual art.

We talked pop culture and theory and abstracted notions of ethics, but we also did the difficult work of translating that theory into practical tools, all while challenging the idea that any simple checklist could be enough to get people through thorny social issues. We talked about cultivation of appreciation for the humanities within the STEM fields. We had the opportunity to sit and build thought maps, to talk practically about what it would take for the team leaders to be able to take these concerns and new modes of thinking back to their companies and teams and bosses and direct-reports and get them to put these things into practice right now. How we can build curricula for educating design teams and weaving knowledges together to teach new computer science and engineering students to think in a truly interdisciplinary way about the kinds of work they do and will do in the very near future.

If I had to put a fine point on it, my ultimate wish is that this could have been multiple weeks of these amazing people, all in context and conversation with each other’s continually deepening contexts and conversation, continuing to deepen each others’ contexts.

Yeah. Like that.

[Image of sticky it notes on a floor-to-ceiling glass windows through which are seen green hills, a river, boulders, a forest, and mountains. The Left column of sticky notes consists of “Neurodiversity + A.I.: Building nonstandard minds,” “Gender + AI,” and “AI + Consent;” this column is labeled “Fuzzy Difficult Stuff.”]

Of the 20 of us in the room, 11 were men, and 9 were women or nonbinary individuals—which, if you know anything about the social dynamics of technology, is a fucking astounding display of equality and representation—but issues of nonbinary gender presentation and acceptance, neurodivergence, and race (I was the only black person) were real. And that’s not to even mention that I don’t know how many people present specifically identified as disabled, because it never came up. That is, itself, a problem.

And so those of us who were the onlies in the room, in a genuine desire to engage and be present in these conversations had to continually codeswitch between a shared only-ness and a communication of what that means to the others in the group who have an appreciation for what that means, but not a direct lived experience of what it’s like.

But:

But this retreat was comprised of a group of people who are all deeply invested in the idea of coming to understand what they don’t understand and then taking the knowledge of what they don’t know, going back out into the world with it, and providing space for the people who understand it and do know it to express their knowledge and be respected as valid sources and candidates of knowledge, believed in their knowledge, and then heeded when they make recommendations based upon their knowledge.

These are people who listened to each other through things that were, again, difficult and personal and intensely nuanced, and came through it not just pretending to have taken it in, but having actually taken it all in, gone back, thought about it more, turned it around, come up with implementations and communications strategies, and then gone back to their interlocutors and said, “So based on what we talked about, before, what do you think of this?”

During the wrap-up session at the end of the retreat, the very first specific thing Andy asked us to reflect on (and which I tried to intensely and directly reinforce, after he asked it), was who wasn’t here. What voices and perspectives and lived experiences weren’t in the room? Who would benefit from being in a room like this? Who does a room like this need? Who is not currently being regarded and heeded who absolutely should be?

Real communication toward trying to understand and implement new perspectives.

And all of this in the space of roughly four days of meals, workshops, hikes, and end-of-the-day conversational unwinding.

Rarely have I ever had such an easy time convincing people that we need a truly intersectional engagement of lived experience if we’re going to try to build new kinds of minds, such that we were able to almost immediately move onto “And what does a genuine non-tokenistic engagement of that look like, in practice?”

At many points throughout the week, we talked about the social forces at play in how technological systems get conceived, built out, and then iterated, and we all understood how much of our problems with machine minds are going to be human problems. Problems of teaching and rearing and training. These were folx who easily recognized that understanding the alterity of other minds, now, in “nonstandard” humans or humans who have been Othered, and in nonhuman animals, is the only chance we’ll have to build the skills of looking for and thinking about minds in unexpected ways. In fact, we spent a great deal of time looking at the history of othering and the things it’s used to do and the things it does, itself, and how that plays out around the world, in different cultures.

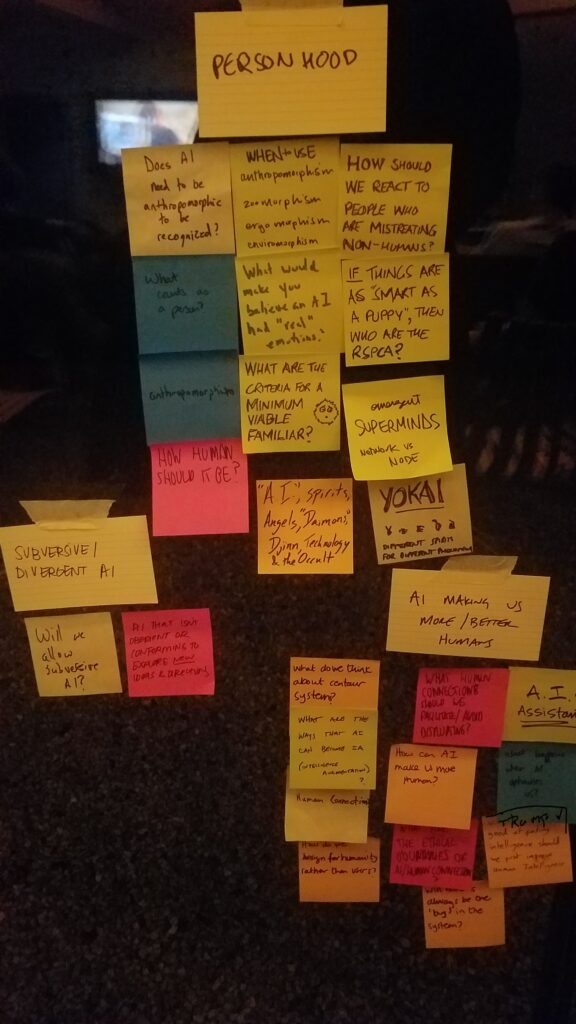

[Image of the cluster labeled “Personhood,” consisting of questions about anthropomorphism, how to react to the mistreatment of nonhumans, what counts as a person and when, what counts as a mind or as “real” emotions, other examples of nonbiological minds down through history and across cultures. There are also other clusters of notes and questions about disobedience and values and what even constitutes a “Good” A.I.]

I am so very glad to have met all of these people, and they not only reinforce my knowledge that the weird interdisciplinary work so many of us are trying to do is worth doing, but they make me feel that there are people in the technosciences who very clearly understand that, and want to do that work with us.

And that is fucking invaluable.

Until Next Time.

Pingback: My Appearance on The Machine Ethics Podcast’s A.I. Retreat Episode | A Future Worth Thinking About