(Cite as: Williams, Damien P. “SFF and STS: Teaching Science, Technology, and Society via Pop Culture,” talk given at the 2019 Conference for the Society for the Social Studies of Science, September 2019)

[Damien Patrick Williams]

Thank you, everybody, for being here. I’m going to stand a bit far back from this mic and project, I’m also probably going to pace a little bit. So if you can’t hear me, just let me know. This mic has ridiculously good pickup, so I don’t think that’ll be a problem.

So the conversation that we’re going to be having today is titled as “SFF and STS: Teaching Science, Technology, and Society via Pop Culture.”

I’m using the term “SFF” to stand for “science fiction and fantasy,” but we’re going to be looking at pop culture more broadly, because ultimately, though science fiction and fantasy have some of the most obvious entrees into discussions of STS and how making doing culture, society can influence technology and the history of fictional worlds can help students understand the worlds that they’re currently living in, pop Culture more generally, is going to tie into the things that students are going to care about in a way that I think is going to be kind of pertinent to what we’re going to be talking about today.

So why we are doing this:

Why are we teaching it with science fiction and fantasy? Why does this matter? I’ve been teaching off and on for 13 years, I’ve been teaching philosophy, I’ve been teaching religious studies, I’ve been teaching Science, Technology and Society. And I’ve been coming to understand as I’ve gone through my teaching process that not only do I like pop culture, my students do? Because they’re people and they’re embedded in culture. So that’s kind of shocking, I guess.

But what I’ve found is that one of the things that makes students care the absolute most about the things that you’re teaching them, especially when something can be as dry as logic, or can be as perhaps nebulous or unclear at first, I say engineering cultures, is that if you give them something to latch on to something that they are already from with, they will be more interested in it. If you can show to them at the outset, “hey, you’ve already been doing this, you’ve already been thinking about this, you’ve already encountered this, they will feel less reticent to engage with it.”

You’ve all already done this, you have made references in your classes. If you are teachers you have in conversations with those, you’re trying to explain your topics to made references to shared cultural knowledge. And sometimes if you are teaching people who are far younger than you, you’ve probably also experienced the shock of having what you thought was a shared cultural meal, you fall completely flat. About five years ago, I tried to make a reference to the matrix to a class of undergrads and they all gave me blank stares. And I was very sad.

So. What teaching with science fiction and fantasy, what teaching with popular culture, as a lens on to STS topics gives us is then not just a way to keep our own cultural references hip and current, but it gives a way for the students that we’re talking to, to connect their current cultural milieu with the history of a broader culture, and to see then how cyclically that broader culture and the science and technology that they have been steeped in, over the course of their lives has been in conversation with each other for longer than they themselves have been alive. How the conversations around science, technology, science, fiction, fantasy, the production of media, the consumption of media, the trends in how media gets taken up in culture more broadly, all of these things help shape—and be shaped by—each other. And if you can show them that—those students who otherwise might not have been taking this class, if the intro course or a second level course that they just need to fill for a requirement—those are the students you can kind of grab in and say, “no, this is something that actually matters to you; this is something that is of interest to you already, and here’s where you can find the thing that you already care about within it.”

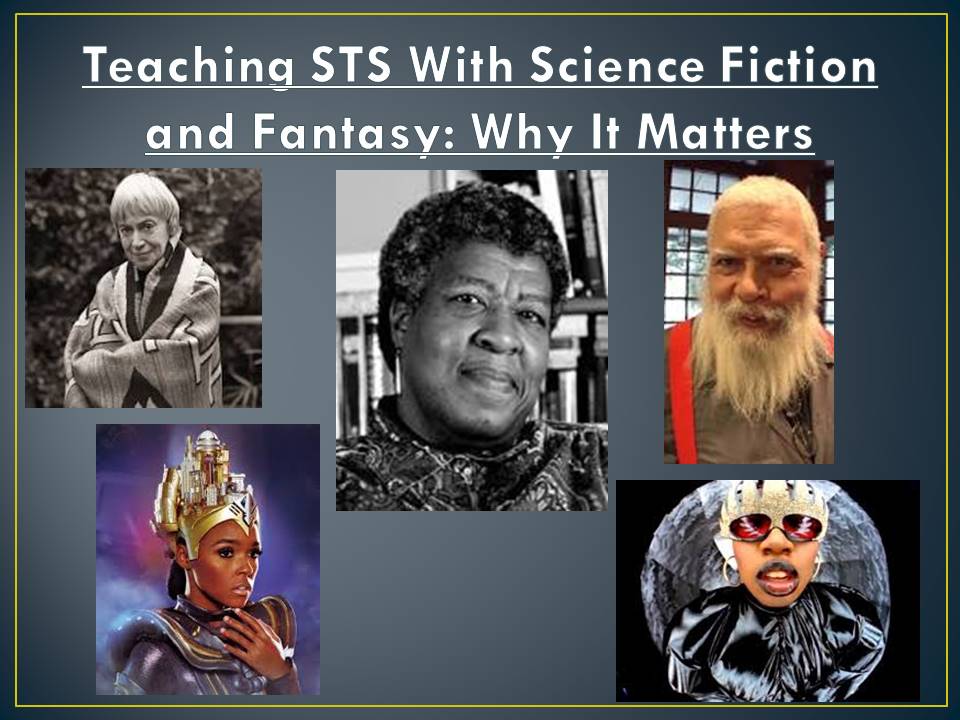

Here I have pictures of a few of the most seminal science fiction and fantasy creators of the 20th and 21st century, we have going clockwise from top left, Ursula K Le Guin, Octavia Butler, Samuel Delaney, Missy Elliott, and Janelle Monáe.

If you can show a student, the arc from here to here [arcs a laser pointer from Le Guin around to Monáe], and from here [indicates Monáe] to Lizzo? And you can show them how the techniques—the recording industry techniques, the production of video techniques, the ways that these people are making the stories and narratives that they are making—are all connected and how they are tied in already to the history and the sociology, and the philosophy of technology and science? Then you have them.

What I’m going to do next is I’m going to go through general intro topics in Science, Technology and Society, and I’m going to talk about just a few examples that can be used to kind of bring thoughts in, bring students in, that they might a) already have familiarity with, and b) not be quite familiar with, maybe have heard about, and thus bring them in a little bit further. And then we’re going to end with a just a very simple example of how to put this into practice in a class.

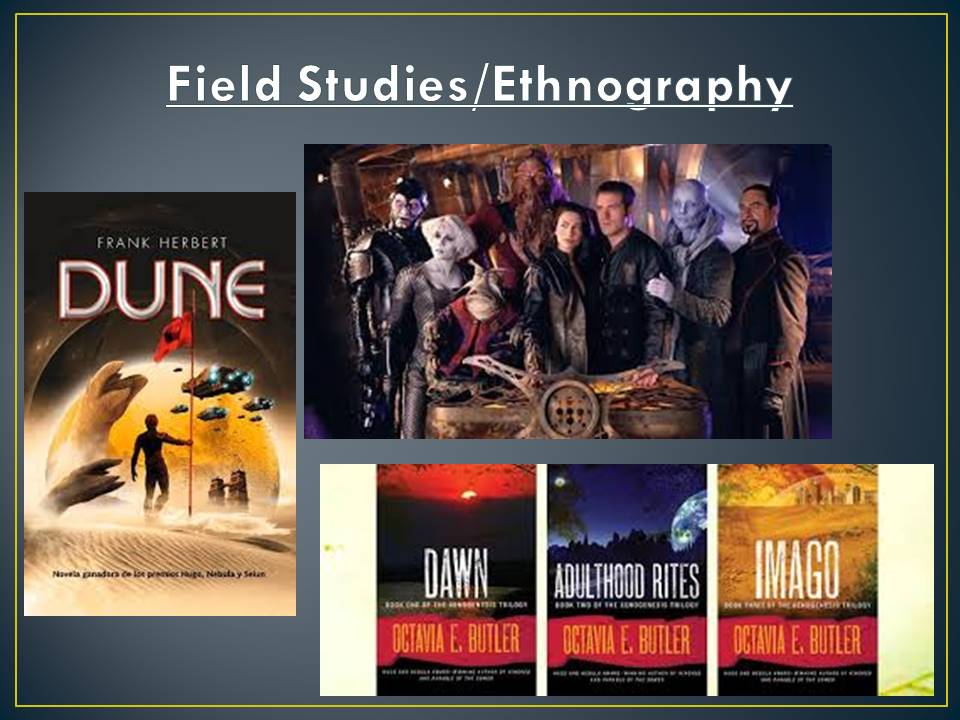

So the first thing we’re going to talk about is field studies and ethnography… and its problems.

If you want to talk to a student about what it means to go out into a culture and experience, the culture, context, and its creations and its notions of how to navigate and understand the world, what we in a Western mode might call “science and technology,” then there are three things that occurred to me at the top of my mind for being embedded observers. One, because I’ve been watching it again for I don’t know how many time is Farscape.

This was a an Australian/American TV show that started in the early 2000s. It was created by the Henson Company—that is Brian and Jim Henson’s company—in joint collaboration with the Sci Fi network. It’s about an ostensibly American, white, male astronaut, who gets, through his own foibles, shot into space and placed in a context in which he has absolutely no understanding, and everything that made sense to him, no longer does, including the fact of how he got there. He is then forced literally every day of his life, to weave himself into a brand new cultural context; to sit, observe and understand through observation, the world around him, or you know, die. So that’s kind of an extreme example of someone who must be embedded to learn, and make knowledge happen, from there.

You also have Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis Saga, in which the embedded observation goes two ways. You have humans who are embedded in an alien context, but you have aliens who have been embedded in a human context, making observations for quite some time. And we find that out in the course of the first text. And they have been doing so in order to make certain interventions and changes to better. Well, for various reasons. I’ll just leave it there. This acts as an opportunity to highlight to students that even while you are embedded and observing you are not some distant, objective individual—you are, in fact, by very nature of the work you are doing, engaged in an exchange, and that it requires you to be mindful of the exchange that you are engaged, to be cognizant of the work that you’re doing.

And then we have Frank Herbert’s Dune. Let’s talk about problematic ethnography for a moment.

The idea that happens in Dune is that a Messiah FIGURE comes from the stars, and then is found to be the leader of these “primitive” peoples. One of the things that Herbert does well, to his credit is that he shows that the “primitive peoples” are actually better suited to survive and thrive in the landscape in which they exist, than any outside observer ever could be, and the external observer from the stars has to be guided very carefully, by the person who has the most time? Which unfortunately happens to be a woman in this context. She does the kind of low-level labor of bringing this person up to speed so he doesn’t trip on his own feet and die in the desert.

But, you know, the failure on this, the problematic aspect of ethnography that shows up here is that he becomes no longer someone who it is impossible for him to remain merely an observer, he has to, in fact, become this active participant, but that active participation very quickly becomes an act of colonialization. It becomes an effect of colonialization as we find out exactly why this Messiah story even exists in the first place. And we find out why the family that he is from has been kind of complicit in that act, from the beginning.

It takes on these tones of cultures that not only impose their views on other cultures as they come in to observe them, but also then seek to actively colonially and imperialistically direct those cultures. Dune has its problems as the text but those problems can be used to teach and highlight other aspects that we as STS scholars should be mindful of.

The social construction of knowledge.

When we think about the social construction of knowledge, we think about the ways in which what we know and what we can know is dependent upon the social context in which we exist. There are a few instances that I can think of the show person of interest. What you know, in this series is dependent upon what you know in the world and the context that you have in the world. It starts off as a very kind of baseline police procedural, and very quickly opens itself up to being a lot more weird than that. It’s a lot more about surveillance, and algorithmic knowledge, and artificial intelligence, but until you travel through the series of the show, you don’t really get a clear view of that. But, as you do, it acts as an object lesson that the social context in which you said kind of constructs the things that you are capable of knowing and doing within that context.

We also have a very recent and probably very well known to your students example, Black Panther. The culture of Wakanda—the social context in which Wakanda sits—has a vast array of knowledge that is only available to them, due to the land, the resources, the background, the history, the social context in which Wakanda has come to be. The knowledge that they have generated, the things that they are capable of knowing is entirely dependent upon this and in fact, in many instances are shown to make no sense to outside observers, because they simply don’t have the context for understanding it. When someone who is harmed and their shot and had to have a massive spinal injury, something that would have been life threatening to them with the context of what they consider to be their very advanced medical knowledge, is healed within the matter of about eight hours, that person is shocked and then avaricious to know more about that technology. Can also talk about imperialism in that context in that scene as well, but that’s for later.

And then, there is The Broken Earth Trilogy. It was hard for me not to put NK Jemisin’s The Broken Earth Trilogy on every single one of my slides, because it ism in all honesty, a perfect text for teaching STS through pop culture, it engages in social construction of knowledge, it engages in cultural history, it engages in indigenous knowledge, it engages in feminist STS, it engages in historical contextualization of the production of knowledge, you can find Actor Network Theory within this text. It is huge—it is about 2000 pages and some change long, but it is an easy read. And it is extraordinarily well crafted. It takes place in a very very distant future at a point in which the earth has been altered through the machinations of many different things, natural disaster technology, outside forces of many kinds inside forces of many kinds. And the text, the narrative follows several people’s struggle to survive in this context, and what they know what they learn what they can do within the scope of their world, as they try to survive, based on who they are and where they’re positioned.

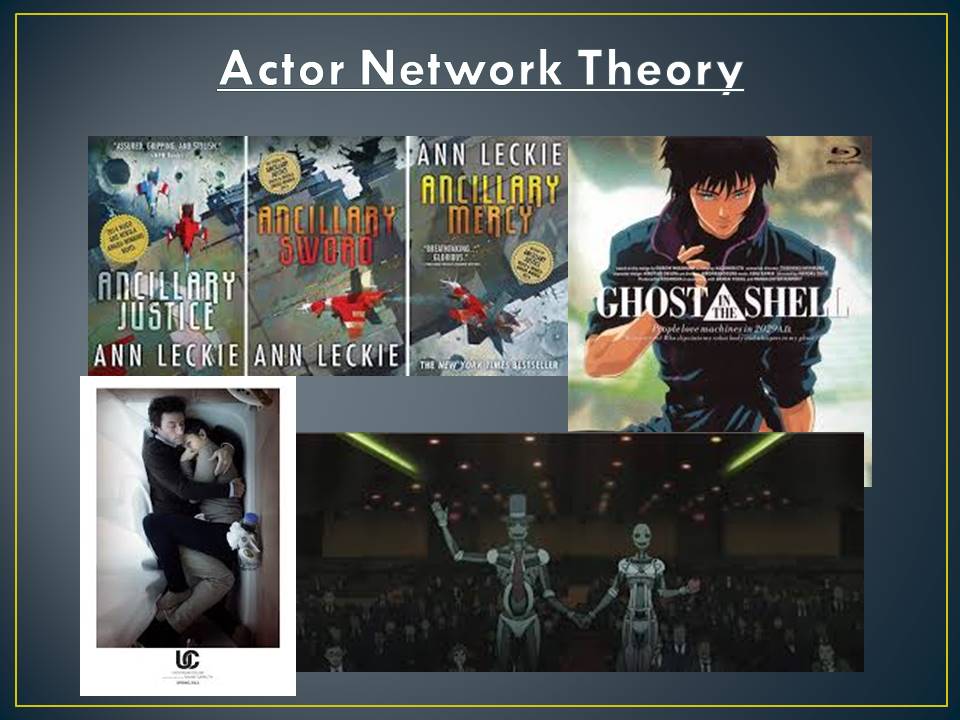

Actor Network Theory.

If you want to teach kids Actor Network Theory—if you want to have them understand it fairly easily.—there are few texts I can think of that work better for this than the Imperial Radch Trilogy by Anne Leckie. It concerns a galactic empire in which the capability of distributing consciousness exists. And that capability can be applied to either artificial algorithmic machine intelligences, or to organic intelligences. Algorithmic machine intelligences can have their consciousness distributed over multiple systems, instantiated and networked, or they can have their consciousness instantiated in organic systems, with the assistance of a little bit of light cyboring in the brains of “volunteer” corpses. And so the question of where the line is drawn between and where the power exists between actors accents, and the network itself becomes very clearly rendered.

We also have the Ghost in the Shell trilogy, which allows for much of the same kind of investigation, but through a more human-centered focus.

We have the Animatrix, specifically the parts of the matrix that concern the AI uprising.

And we have the movie Upstream Color which is the second offering by the director who created Primer, movie about time travel I cannot remember that person’s name of streaming color concerns, a specific type of fungus, plant and human interrelationship that causes very specific experiences of time and space.

Indigenous and post-colonial, decolonial STS.

Who Fears Death? by Nnedi Okorafor concerns a far-future Africa. It is what Nnedi Okorafor has termed “Africanfuturism“—all one word—”Africanfuturism.” Not Afrofuturism; Afrofuturism is different—comes out of questions of the African diaspora, and the African American experience and response to that diaspora.

Both can teach you about visions of the future and technology that gets created in response to having your culture ripped away from you, and trying to survive that colonial imposition.

History ontology and embedded knowledge.

Iron Man. I mean… Iron Man. You teach “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” with Iron Man. Like, that’s just, those are just obvious together.

But you also have Primer, which again I mentioned earlier, but it’s about the knowledge that can be embedded in a piece or a tool or technology that can be surprising to us. And it can be about techniques that are that have surprising interventions.

We also have the animé, 1988 animé, Akira, which involves the ways in which knowledge and the production of technology are paired, but have a specific history and a specific embedding that borders on the technologically deterministic. So if you want to teach your students about technological determinism, you can use Akira for that.

Feminist STS and situated knowledges. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, obviously.

Once again, The Fifth Season, The Broken Earth Trilogy. Again, I struggled not to put this on everything.

And then Kelly Sue DeConnick’s comic Bitch Planet. It’s a 12 issue comic, it’s about a not-too-distant future in which women are not delineated into “compliant” and “non-compliant” categories. Non compliant women, if they are kind of irreconcilably non compliant are sent off to an all-woman prison in space. And it is about the history and the social context in which that comes to be, but the situated knowledge of what those women in that context, then learn and work and understand about the world, and how it kind of deconstructs this notion of objectivity, these assumptions of what the “default” perspective on the world are.

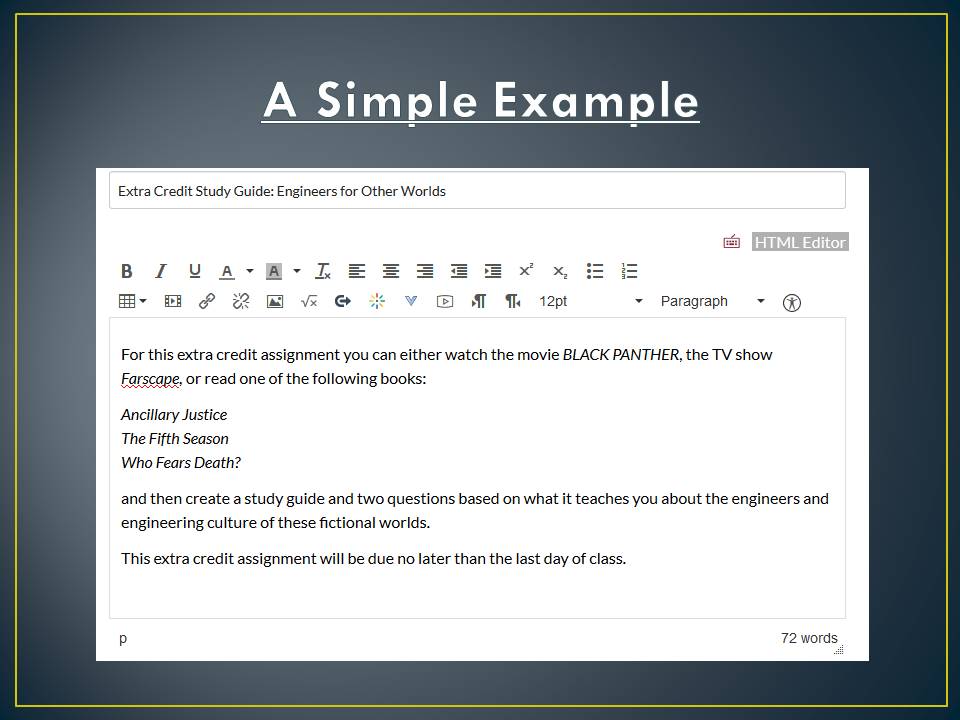

Finally, a simple example of how to put this into practice. This is an extra credit assignment for my students in Engineering Cultures, this year. And this just says:

“For this extra credit assignment you can either watch the movie BLACK PANTHER, the TV show Farscape, or read one of the following books:

“Ancillary Justice

The Fifth Season

Who Fears Death?”

(Those first two are the first books in the Imperial Radch Trilogy, and The Broken Earth Trilogy, respectively)

“and then create a study guide and two questions based on what it teaches you about the engineers and engineering culture of these fictional worlds.

“This extra credit assignment will be due no later than the last day of class.”

This is just a very basic way of putting into practice, “Here is something that you might already have been interested in; here is a way for you to, if you missed an assignment, replace that assignment, with this information.” If I was teaching this class as a whole, if I was teaching Pop Culture STS, this would be the basic template for the majority of the assignments that these students received, rather than a potential extra credit at the end. Since I’m currently teaching engineering cultures, I have to give them a little bit more of a rigid program.

Once again, at the end of the day, this is all about meeting the students where they are, where they want to be, where you want them to be, and bringing all of those together to get them to understand that STS has already been a part of their daily lived experience, and that you have already been experiencing this with them, and finding a way to have that conversation be enjoyable, engaging, and fun for all of you. Thanks.

[General Applause]

[Shannon Conley, Moderator]

All right. Let’s just take a couple of questions for Damien.

[Questioner 1]

… One of the problems I ran into was they had this very rigid fiction/nonfiction line, where fiction is lies, and non fiction is truth. And therefore, other than like, one person who had all sorts of other problems in her conceptions of the world, they rejected the whole premise of me trying to cross those boundaries. I’m wondering how you get them to engage.

[DPW]

So for the most part, I haven’t had such, I haven’t had anybody that has such a hardcore divide, or at least not a whole class of anybody who’s had that hardcore of a divide between fiction and nonfiction. But one of the things that is kind of fundamental to—again, I started as philosopher by training, and moved into STS from there. But one of the things that it’s kind of like a baseline, you know, aim, if not assumption, that sits under this is that the nature of the stories that we tell, the narratives that we use to talk about the world, shape the world that we then talk about.

And so I think that one of the key things is how you can talk to them—and you know, you can move Mary Shelley up to the very beginning, if you want—and you can talk about the fact that Mary Shelley’s work was shaped by the work that her father and mother had been doing, by the cultural context of the people that she’d been working with, and how that work has then turned into a whole conversation about artificial life, artificial intelligence, what it means to create something. The fact that we use the term “Frankenfoods,” in the world. Like… These things are now because of a story, because of a narrative, because of what those students might consider to be “lies.” And if you can show them that kind of cyclical connection, and how it’s never going to be disentangled in a clean and neat way, like that—that they’re always going to inform each other— then you have at least a starting point, and you can move from there.

And then they can probably think for themselves of some other examples where, you know, stories that they might be familiar with, fiction that they might be familiar with, has come to be part of the wider cultural middle you and directed the conversation about elements of science and engineering that they might be interested in going on to teach and talk about with other students.

[Questioner 2]

I just wanted to add to this conversation because we teach a class that does start with Marry Shelley’s Frankenstein.

[DPW]

Nice!

[Q2]

And we follow it up with The Iron Giant. Very nicely paired together, by the way And our entire thesis to these students is this: is that we can figure out how our feelings about these stories, and understanding of these the stories then influence design, implementation policy, decision making, etc. And yet.We do this for an entire semester, and we still have what? Like, you know, five or six, but still stumble, you know, connecting back to the actual real world. So, tomorrow morning, at the same time, we’re going to have to also have this conversation of like, what, like, “how do we get through this stumbling block of, ‘this is fiction, this is real.'”

[DPW]

I don’t remember who I saw next.

[Unknown audience member]

I think we all want to respond to you [the first and second questioners].

[SC]

Also in the interest of time, maybe just do two more questions for Damien,so we can make sure Marissa gets full time, and then we’ll maybe bring it all back together.

[DPW]

Yeah, exactly. Kristen, I think you were the first one I saw and then I don’t know your name…

[Kristen Koopman]

I just had a very quick comment that might address that: David Kirby’s done a lot of work on the role of the depiction of technologies in science fiction as preparing cultures to then take up those technologies, and if you search “David Kirby” and “diegetic prototypes,” that’s a whole [inaudible] that might be an easy offering.

[DPW]

“David Kirby.” Thank you.

[Previously Indicated Unknown Questioner 4]

I was actually going to say that.

[General Laughter]

[DPW]

Then we have time for one last one! Who wants to go?

[PIUQ4]

In terms of things that talk about the origins of technologies as rooted in science fiction. So I teach a cyber security and privacy course, and we finish this course by writing fiction. And so I have them pitch to me an idea for a science fiction story that has a relevance to policy, culture, labour, society, something like that, and then I have them discuss it. And I give them science fiction to read based on the kinds of topics they’ve been interested in.

But! They still everything as fine and normal, until I give them fiction to write, and then, it’s blocked. Right? I mean, for some people.

[SC]

And maybe, Damien, maybe you can keep fielding questions while Marissa gets set up?

[DPW]

Yeah, I’m gonna get out of this way. Do you have the…?

[Questioner 5]

Can I add Emily Martin’s The Egg and the Sperm? Even though it’s an older instance [?], it’s one of the turning points for them, in terms of how narratives and discourses change the structure of scientific…

[Audience Member]

It blew my mind 20 years ago

[Q5]

And it’s still, you read it now and you go… It’s still…

[DPW]

But um, yeah no, the, I think one of the things that’s come up the the, until you get to the end, and doing the science fiction component is, and, you know, Kristen, you know, this, and there’s, I think someone else in here does literature as well, and I’m missing who cuz I’m very tired. But, um, there’s, I mean, it’s a skill. If a student has never really sat down to do writing work of that type before, that’s not going to just come out for them. Some people might have a, more of an affinity for it than others, but it’s still going to, there’s still going to have to be this process of them getting used to it.

So I think one of the things that I really liked the idea that you’ve laid out there, I think that’s a really, really good plan for going about that. I think, like if I if I take it up, the one in, the one change I would make is try to work in smaller writing and revising of fiction, from the first day, and just try to get them to like, be doing it throughout, and then have that like, you know, bigger thing at the end to be the product of that.

Still probably going to turn into a lot of fluff, like you’re gonna get a lot of fluff from people at the end of it, who are just kind of phoning that that aspect in. But I think you might also maybe spark somebody don’t want to do that more often on the regular.

[Q5]

I’m just saying, some students see it as fluff at the end, and I like, want them entertained[?] at the end.

[DPW]

Yeah. That’s so frustrating. That’s, yeah, we’ll do this more. Thank you.