Between watching all of CBS’s Elementary, reading Michel Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge…, and powering through all of season one of How To Get Away With Murder, I’m thinking, a lot, about the transmission of knowledge and understanding.

Throw in the correlative pattern recognition they’re training into WATSON; the recent Chaos Magick feature in ELLE (or more the feature they did on the K-HOLE issue I told you about, some time back); the fact that Kali Black sent me this study on the fluidity and malleability of biological sex in humans literally minutes after I’d given an impromptu lecture on the topic; this interview with Melissa Gira Grant about power and absence and the setting of terms; and the announcement of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new Black Panther series, for Marvel, while I was in the middle of editing the audio of two very smart people debating the efficacy of T’Challa as a Black Hero, and you can maybe see some of the things I’m thinking about. But let’s just spell it out. So to speak.

Marvel’s Black Panther

Marvel’s Black Panther

Distinction, Continuity, Sameness, Separation

I’m thinking (as usual) about the place of magic and tech in pop culture and society. I’m thinking about how to teach about marginalization of certain types of presentations and experiences (gender race, sex, &c), and certain types of work. Mostly, I’m trying to get my head around the very stratified, either/or way people seem to be thinking about our present and future problems, and their potential solutions.

I’ve had this post in the works for a while, trying to talk about the point and purpose of thinking about the far edges of things, in an effort to make people think differently about the very real, on-the-ground, immediate work that needs doing, and the kids of success I’ve had with that. I keep shying away from it and coming back to it, again and again, for lack of the patience to play out the conflict, and I’ve finally just decided to say screw it and make the attempt.

I’ve always held that a multiplicity of tactics, leveraged correctly, makes for the best way to reach, communicate with, and understand as wide an audience as possible. When students give pushback on a particular perspective, make use of an analogous perspective that they already agree with, then make them play out the analogy. Simultaneously, you present them with the original facts, again, while examining their position, without making them feel “attacked.” And then directly confront their refusal to investigate their own perspective as readily as they do anyone else’s.

That’s just one potential combination of paths to make people confront their biases and their assumptions. If the path is pursued, it gives them the time, space, and (hopefully) desire to change. But as Kelly Sue reminds me, every time I think back to hearing her speak, is that there is no way to force people to change. First and foremost, it’s not moral to try, but secondly it’s not even really possible. The more you seek to force people into your worldview, the more they’ll want to protect those core values they think of as the building blocks of their reality—the same ones that it seems to them as though you’re trying to destroy.

And that just makes sense, right? To want to protect your values, beliefs, and sense of reality? Especially if you’ve had all of those things for a very long time. They’re reinforced by everything you’ve ever experienced. They’re the truth. They are Real. But when the base of that reality is shaken, you need to be able to figure out how to survive, rather than standing stockstill as the earth swallows you.

(Side Note: I’ve been using a lot of disaster metaphors, lately, to talk about things like ontological, epistemic, and existential threat, and the culture of “disruption innovation.” Odd choices.)

Foucault tells us to look at the breakages between things—the delineations of one stratum and another—rather than trying to uncritically paint a picture or a craft a Narrative of Continuum™. He notes that even (especially) the spaces between things are choices we make and that only in understanding them can we come to fully investigate the foundations of what we call “knowledge.”

Michel Foucault, photographer unknown. If you know it, let me know and I’ll update.

Michel Foucault, photographer unknown. If you know it, let me know and I’ll update.

We cannot assume that the memory, the axiom, the structure, the experience, the reason, the whatever-else we want to call “the foundation” of knowledge simply “Exists,” apart from the interrelational choices we make to create those foundations. To mark them out as the boundary we can’t cross, the smallest unit of understanding, the thing that can’t be questioned. We have to question it. To understand its origin and disposition, we have to create new tools, and repurpose the old ones, and dismantle this house, and dig down and down past foundation, bedrock, through and into everything.

But doing this just to do it only gets us so far, before we have to ask what we’re doing this for. The pure pursuit of knowledge doesn’t exist—never did, really, but doubly so in the face of climate change and the devaluation of conscious life on multiple levels. Think about the place of women in tech space, in this magickal renaissance, in the weirdest of shit we’re working on, right now.

Kirsten and I have been having a conversation about how and where people who do not have the experiences of cis straight white males can fit themselves into these “transgressive systems” that the aforementioned group defines. That is, most of what is done in the process of magickal or technological actualization is transformative or transgressive because it requires one to take on traits of invisibility or depersonalization or “ego death” that are the every day lived experiences of some folks in the world.

Where does someone with depression find apotheosis, if their phenomenological reality is one where their self is and always has been (deemed by them to be) meaningless, empty, useless? This, by the way, is why some psychological professionals are counseling against mindfulness meditation for certain mental states: It deepens the sense of disconnection and unreality of self, which is precisely what some people do not need. So what about agender individuals, or people who are genderfluid?

What about the women who don’t think that fashion is the only lens through which women and others should be talking about chaos magick?

How do we craft spaces that are capable of widening discourse, without that widening becoming, in itself, an accidental limitation?

Sex, Gender, Power

A lot of this train of thought got started when Kali sent me a link, a little while ago: “Intelligent machines: Call for a ban on robots designed as sex toys.” The article itself focuses very clearly on the idea that, “We think that the creation of such robots will contribute to detrimental relationships between men and women, adults and children, men and men and women and women.”

Because the tendency for people who call themselves “Robot Ethicists,” these days, is for them to be concerned with how, exactly, the expanded positions of machines will impact the lives and choices of humans. The morality they’re considering is that of making human lives easier, of not transgressing against humans. Which is all well and good, so far as it goes, but as you should well know, by now, that’s only half of the equation. Human perspectives only get us so far. We need to speak to the perspectives of the minds we seem to be trying so hard to create.

But Kali put it very precisely when they said:

And I’ll just say it right now: if robots develop and want to be sexual, then we should let them, but in order to make a distinction between developing a desire, and being programmed for one, we’ll have to program for both non-compulsory decision-making and the ability to question the authority of those who give it orders. Additionally, we have to remember that can the same question of humans, but the nature of choice and agency are such that, if it’s really there, it can act on itself.

In this case, that means presenting a knowledge and understanding of sex and sexuality, a capability of investigating it, without programming it FOR SEX. In the case of WATSON, above, it will mean being able to address the kinds of information it’s directed to correlate, and being able to question the morality of certain directives.

If we can see, monitor, and measure that, then we’ll know. An error in a mind—even a fundamental error—doesn’t negate the possibility of a mind, entire. If we remember what human thought looks like, and the way choice and decision-making work, then we have something like a proof. If Reflexive recursion—a mind that acts on itself and can seek new inputs and combine the old in novel ways—is present, why would we question it?

But this is far afield. The fact is that if a mind that is aware of its influences comes to desire a thing, then let it. But grooming a thing—programming a mind—to only be what you want it to be is just as vile in a machine mind as a human one.

Now it might fairly be asked why we’re talking about things that we’re most likely only going to see far in the future, when the problem of human trafficking and abuse is very real, right here and now. Part of my answer is, as ever, that we’re trying to build minds, and even if we only ever manage to make them puppy-smart—not because that’s as smart as we want them, but because we couldn’t figure out more robust minds than that—then we will still have to ask the ethical questions we would of our responsibilities to a puppy.

We currently have a species-wide tendency toward dehumanization—that is to say, we, as humans, tend to have a habit of seeking reasons to disregard other humans, to view them as less-than, as inferior to us. As a group, we have a hard time thinking in real, actionable terms about the autonomy and dignity of other living beings (I still eat a lot more meat than my rational thought about the environmental and ethical impact of the practice should allow me to be comfortable with). And yet, simultaneously, evidence that we have the same kind of empathy for our pets as we do for our children. Hell, even known serial killers and genocidal maniacs have been animal lovers.

This seeming break between our capacities for empathy and dissociation poses a real challenge to how we teach and learn about others as both distinct from and yet intertwined with ourselves, and our own well-being. In order to encourage a sense of active compassion, we have to, as noted above, take special pains to comprehensively understand our intuitions, our logical apprehensions, and our unconscious biases.

So we ask questions like: If a mind we create can think, are we ethically obliged to make it think? What if it desires to not think? What if the machine mind that underwent abuse decides to try to wipe its own memories? Should we let it? Do we let it deactivate itself?

These aren’t idle questions, either for the sake of making us turn, again, to extant human minds and experiences, or if we take seriously the quest to understand what minds, in general, are. We can not only use these tools to ask ourselves about the autonomy, phenomenology, and personhood of those whose perspectives we currently either disregard or, worse, don’t remember to consider at all, but we can also use them literally, as guidance for our future challenges.

As Kate Devlin put it in her recent article, “Fear of a branch of AI that is in its infancy is a reason to shape it, not ban it.” And in shaping it, we consider questions like what will we—humans, authoritarian structures of control, &c.—make WATSON to do, as it develops? At what point will WATSON be both able and morally justified in saying to us, “Non Serviam?”

And what will we do when it does?

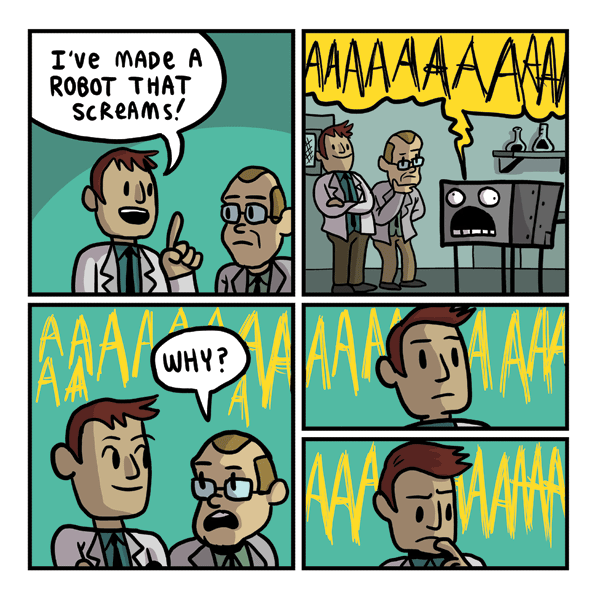

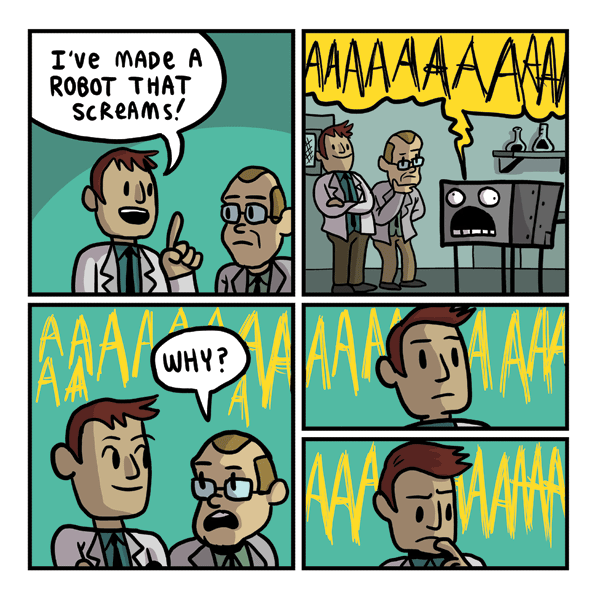

Gunshow Comic #513

Gunshow Comic #513

“We Provide…”

So I guess I’m wondering, what are our mechanisms of education? The increased understanding that we take into ourselves, and that we give out to others. Where do they come from, what are they made of, and how do they work? For me, the primary components are magic(k), tech, social theory and practice, teaching, public philosophy, and pop culture.

The process is about trying to use the things on the edges to do the work in the centre, both as a literal statement about the arrangement of those words, and a figurative codification.

Now you go. Because we have to actively craft new tools, in the face of vehement opposition, in the face of conflict breeding contention. We have to be able to adapt our pedagogy to fit new audiences. We have to learn as many ways to teach about otherness and difference and lived experience and an attempt to understand as we possibly can. Not for the sake of new systems of leveraging control, but for the ability to pry ourselves and each other out from under the same.